A conservator is often trusted to determine what something is, where it comes from, and the time period in which it was made. And while we are not antiques dealers, nor can we give an estimated sales price (a la "Antiques Road Show"), it is often a conservator who is sought to weigh in on the authenticity of an item, simply from the perspective of an expert who is in close working contact with artifacts on a daily basis.

Recently, I watched a fellow textile expert look at a textile composed of silk and wool. The owner had hoped the artifact was from a particular time period, and it was quite likely to be, but the provenance of the piece was largely unknown. It was not until after the examination of this textile that the expert asked for the "story". So as not to be biased by the hopes of the owner, this expert based their examination on the hard evidence: thread count, weave structure, dyes used, degradation of the silk areas, stitching methods, style of the piece, hems, selvedge ends, (and other things that textile folks find fascinating!).

In a blog post written not long ago, we spoke of

dating objects and our research into the "sprang" weave structure of a sash from the War of 1812. That blog post has received 1000's of views, and lots of comments and emails asking us about the dates of similar objects. In the studio at the same time was a beaver felt-style chapeau with "1812" prominently sewn to the front flap with a lovely decorative cord. And while it would be easy to say it was from 1812, that was not the case. From observation alone, the hat was quite worn and featured the date to commemorate the War of 1812, that was certain. But was it worn in battle? That seemed unlikely from several factors: the materials used to construct the hat, the condition of the hat, the rank of the owner, and the style of the hat was from a slightly later period (so while it was similar, it had distinctly later features). Our findings were discussed in our blog

"what's in a date?".

|

| Was this hat worn in the War of 1812, or does it commemorate the War of 1812? |

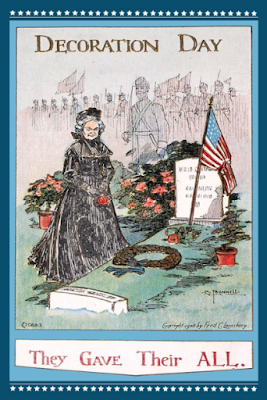

There are many items that commemorate dates, like the 1812 hat above, that can easily be thought to originate at the time or event they commemorate. Such is the case with flags, pennants, buttons, banners and other items that are reproduced for a celebration, especially a centennial or significant anniversary.

On the other hand are objects that have a strong story or a label that was affixed to the object a long time ago. These are items that have history from legend retold or sometimes from documentation that is quite old, but does not go back to the date of the object.

For example, a lovely textile, which came into the studio along with some other artifacts, was believed by the owner to be something quite extraordinary. For this owner, family tradition had cemented the importance of the garment they believed to be from the late 13th century. Yet, the story (which was beautiful and had accompanying documentation that dated to the mid 1800's) was not plausible for a variety of reasons. The most persuasive factor was that this artifact was made using a technique that was not known until hundreds of years later. Also this textile was in very good condition, yet was hoped to be a 740 year old garment.

|

A lovely knitted garment with open work and ribbed scalloped edges. Family

history claimed it was knit by a queen in the late thirteenth century. |

It was a surprise to the owner that another item in their collection was actually older, and was the one that was remarkable. This textile (photo detail below) was used as a protective covering to hold a circa 1800 book. The covering is a pouch made of linen with silk, and the embroidery is wonderful. When we commented on it, the owner stated that the textile was always "just the bag used to protect the book". The bag was clearly not made for the book, the book just happened to fit inside and so the two are now, and for many past decades, "together".

|

Detail of the small embroidered pouch. The owner was surprised that it

was possibly a 17th century piece depicting King David playing his harp. |

Sometimes an item will be misidentified as something it is similar to, but is not: "Japanese Kimono", "Tapestry", "battle flag", etc. will turn out to be a Chinese robe or a weaving that was hung on the wall, or a flag made to commemorate a military unit. These long standing labels can be difficult to shed. And often it is difficult to tell the client that what they have is not exactly what they think they have. However, the history of the object is still there, it's just different than what was assumed, but certainly just as (and sometimes more) interesting.

|

| Is this a Revolutionary War era flag because it features 13 stars? One must be cautious that the number of stars, does not automatically mean the flag is from that specific time period. Flags, like the 1812 chapeau above, are often made to commemorate the anniversary of an event. |

Depending on the artifact, whether it be a textile, object, paper etc. Particular attributes are important. Objects made of wood, metal, glass or any medium all have specific characteristics that are indicative of the way they were made, and often when they were made. As discussed above, textiles can be quite telling when you look at the way they are woven, the fabric they are composed of, or the way they are dyed.

Why is dye analysis so important and what can be learned from it? Dye analysis is not meant to tell the date something was dyed, instead it is used to determine if a dye is natural or synthetic. We know that synthetic dyes were discovered in 1856. This is a clear date line because regardless of the appearance of an item, if the dye present in it is synthetic then the item absolutely cannot be dated before 1856.

More so than analysis, or even hard facts, is the simple fact that you must remain unbiased from trying to

make an artifact fit into a particular era. For example, recently an item came to us that had been framed. The item was believed to be of a particular time because of the frame. However, the item was separate from the frame, yet because they had been together for so long they were assumed to be one in the same.

Determining an artifact's authenticity or period of manufacture or era can be quite difficult (if not impossible) without supporting documentation or a lot of unbiased research. Bias is a dangerous thing, hence is why scientists guard against it in their research to remove their predispositions from the outcome. It is no less dangerous in attempting to prove validity in dating artifacts, proving authenticity or establishing provenance.

_____________________________

Gwen Spicer is a textile conservator in private practice. Spicer Art Conservation specializes in textile conservation, object conservation, and the conservation of works on paper. Gwen's innovative treatment and mounting of flags and textiles is unrivaled. To contact her, please visit her website.