by Barbara Owens

What does a conservator do with a one-of-a-kind piece of

American history from the greatest inventor of all time? Let me tell you.

The date is June 22, 1878.

Thomas Edison is perfecting his phonograph, a machine that

will literally change the future and the recording of voice, music and sound,

as we know it. Edison is not

without his critics. Then, just as

today, people resist change and many are not sure about Edison’s new

device. Edison however knows that

his invention will change the world.

It is not known for sure where Edison is on this exact day. But it is believed he is in St. Louis,

one of many stops he makes to demonstrate (and hopefully find buyers for) his

revolutionary new device.

The following is an excerpt from an interview Edison had

given earlier in 1878 when he spoke to a Washington

Post reporter in Washington DC.

Edison speaks to the reporter while at the Smithsonian where he is to

demonstrate his new invention.

Here Edison describes in his own

words how the phonograph works, including the role of the tinfoil in the

recording of sound:

When do you give an exhibition of your

phonograph?"

"At 4 o'clock. Have you ever seen

it? Well, come in and I'll show it to you." And leading the

way, he (Edison) entered the room adjoining the secretary's office, uncovered

the wonderful "Sound Writer," and began to explain it.

"Here the phonograph, you see, is a thin

disc or diaphragm of iron, beneath which is this fine steel point, which moves

up and down by the vibrations of the disc. Beneath this is the revolving

cylinder, on which is this spiral groove. On the axis of the cylinder is

a screw, the distance between the threads being the same as the distance

between the grooves on the cylinder. The cylinder is covered with a sheet

of tin foil--you will see it operate by and by--and when the cylinder is

revolved the steel point presses the tin-foil into the spiral groove. If

now the diaphragm be made to vibrate by the voice the steel point makes a

series of indentations in the tin-foil grooves, corresponding to the sounds

uttered. On going over again the same groove with the steel point, by

setting the cylinder again at the starting point, that is, by going over the

same ground, the indentations in the tin-foil cause the membrane again to

vibrate precisely as at first, thus reproducing the sound originally

made. The same sound wave you first made is returned to you in whatever

shape you made it. Your words, for example, are preserved in the

tin-foil, and will come back upon the application of the instrument years after

you are dead in exactly the same voice you spoke them in."

"How many times?"

"As long as the tin-foil lasts.

This tongueless, toothless instrument, without larynx or pharynx, dumb,

voiceless matter, nevertheless mimics your tones, speaks with your voice,

utters your words, and centuries after you have crumbled into dust will repeat

again and again, to a generation that could never know you, every idle thought,

every fond fancy, every vain word that you choose to whisper against this thin

iron diaphragm."

"How old are you, Mr. Edison?"

"Thirty-one."

"Very young yet."

"I am good for fifty; and I hope to astonish

the world yet with things more wonderful than this. I think the world is

on the eve of grand and immense discoveries, before whose transcendent glories

the record of the past will fade into insignificance. This is a very poor

specimen of a phonograph, however. You see how simple the mechanism of

this idea, and how simple the idea itself; and yet, after all, it is

curious."

And the reporter, turning away to record the

utterances of the sages in the room adjoining, thought of that passage of Holy

Writ which says, "every idle thought and every vain word which man thinks

or utters are recorded in the Judgment Book." Does the Recording

Angel sit beside a Celestial Phonograph, against whose spiritual diaphragm some

mysterious ether presses the record of a human life?

Spicer Art Conservation has the pleasure of restoring a full

page of Edison’s “tin foil”! This

particular piece of foil was given in July of 1978 to General Electric’s Hall

of History and then later was moved, with the entire Hall’s Collection, to the

Schenectady Museum and Suits-Bueche Planetarium, which later was renamed the

Museum of Innovation and Science ("miSci").

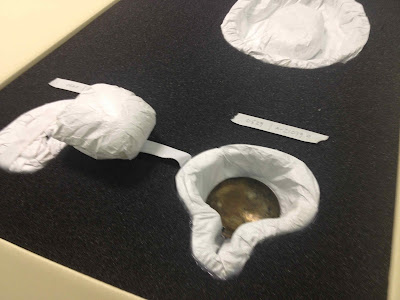

The object’s current condition is clear from the

photographs. It has been folded

for some time into a 5” x 1 7/8” package. Upon folding, the edges were left unsupported; this resulted

in distortion and perpendicular tears.

Further damage occurred when the tinfoil was opened at some point in the

past. The tinfoil then experienced

additional creasing of parallel folds between the tears. Two narrow sections at one end are more

tarnished than the other six sections, this occurred because these sections

were located on the outside of the folded package.

The tinfoil has resided in the climate-controlled archives

of the Schenectady Museum. It is

housed in a flat, acid-free box and lies flat while in the cabinet.

SO WHAT DOES IT SAY????!!!!

The answer (right now) is that no one knows. The goal of Spicer Art Conservation’s

treatment of Edison’s Tinfoil Recording is to flatten as much of it as

possible. The foil was originally

going to be sent to England to be digitally scanned. It will now be sent to the Lawrence National Laboratory

where equipment has been adapted to scan and reproduce the sound from this

incredible American treasure.

Spicer Art Conservation will also create housing for transportation

of the piece. While all of this is

very exciting, it is a bit daunting in that next to nothing is known about this

particular material due to its rarity.

The foil must be flattened by hand with utmost care to preserve the

surface “ticks” that create the sound.

The restoration is time-consuming and painstaking, but more importantly

it is an honor to work on such a rare piece from an iconic figure and legendary

inventor.

This recording is one of only two believed to have survived

in its entirety. The other is

housed in the Smithsonian where Edison demonstrated it some 134 years ago.

And look for more details on the restoration of Edison’s

Tinfoil here in our blog.