by Gwen Spicer

Over the years I have seen mothballs in many collecting institutions and client homes. They are a true "left-over" from a time in the twentieth century where chemicals were thought to solve all of our problems. While mothballs and other chemicals gave the appearance of solving some problems, what they really did was produce a great deal more!

|

| Mothballs. No one should use them, EVER. |

Our awareness of the hazards of chemicals is still quite new. We all have Rachael Carson to thank for her timely publication "Silent Spring" in 1962. It woke us all up to the danger and harm that we were doing to our environment and ourselves. Sadly, it may have not been widely read. 52 years later we continue to use harmful products thinking we are somehow helping.

|

| Rachel Carson, truly a voice ahead of her time. |

After Carson's book, laws were quickly enacted that stopped or limited the use of the most harmful chemicals and pesticides, especially the use of DDT. However, many others still remain on the market. Mothballs are one of these. The little white balls of toxin have been used for decades to deter and kill moths and other insects from damaging wool textiles.

The definition of a mothball is as follows:

Small balls of chemical pesticide and deodorant used when storing clothing and other articles susceptible to damage from mold or moth larvae. They come in two different formulations; one, using naphthalene, and the other using paradichlorobenzene as the active ingredient. Naphthalene, a hydrocarbon derived from coal tar, which easily exudes gas, acts as a fumigant.

So why are mothballs hazardous to your health? Several reasons:

Naphthalene fumes may overwhelm a child wearing a sweater recently removed from a chest containing mothballs. Inhaling the chemical can lead to nausea, vomiting, fatigue, headache, fever, confusion, and fainting. Routine exposure can cause a condition called hemolytic anemia, where a person's red blood cells get damaged. Ingestion or skin exposure causes more extreme reactions in the liver and bladder, causing jaundice, lightheadedness, and eventually leading to coma. Not surprising, but cigarette smoke contains the chemical, which as we know can lead to cancer. So really, there are no health benefits associated with naphthalene.

Toxic nature and damage from use:

Older mothballs consisted primarily of naphthalene, but due to naphthalene's flammability, many modern mothball formulations instead use 1,4-dichlorobenzene, which may be somewhat less flammable. The latter chemical is also variously labeled as para-dichlorobenzene, p-dichlorobenzene, pDCB, or PDB, making it harder to identify unless the purchaser knows these synonyms. Both of these mothball chemicals have the strong, pungent, sickly-sweet odor often associated with mothballs.

Both naphthalene and 1,4-dichlorobenzene are the main ingredient in mothballs because they undergo sublimation, which means that they start in a solid state which evaporates directly into a gas; this particular gas is toxic to moths and moth larvae, hence it is an effective pesticide.

Another version of a mothball, and just as dangerous, is moth crystals. They are made exclusively from paradichlorobenzene (PDB), which is considered even more toxic than naphthalene. Regardless of their toxicity, both chemicals are a poor choice for storage because prolonged exposure of PDB vapors on plastics may melt them, affecting some sweater boxes and other types of plastic; it is therefore not recommended to use on clothes with plastic buttons or decorations. The effects of PDB on humans are not well known, but it is a suspected human carcinogen because it has been shown to cause cancer in animals.

|

An all-too-common sight. Mothballs and the clothes they

are "protecting" sealed tightly in a plastic container |

For the insecticidal chemicals of mothballs to be effective, they need to be placed with the clothing in a sealed container so the vapors can build up and kill the moths. In a sealed atmosphere like this, the vapors are not as harmful to people because they are relatively contained. The main exposures would occur when filling or opening the containers, or from wearing clothes immediately after opening (especially a problem for infants).

Naphthalene mothballs and 1,4-dichlorobenzene mothballs should not be mixed, as they react chemically to produce a liquid (rather than sublimating) that may cause damage to items being preserved. Should this happen to your artifact, the outlook is grim. :(

If that is not bad enough, there are things that make mothballs even worse. Wet mothballs are even more potent than dry ones. And the wetness can be profound, like exposure to water from a flood or leaky pipe, or mild, in the form of high humidity. Either will cause the odor to be more potent and sublimation to be more rapid. This increase in potency puts the person treating or washing the garment at more risk. Similarly, sometimes the garment has not been in moth balls for a long time, but upon wetting for treatment, the chemicals that had been absorbed inside the fibers and had sat dormant, are released.

Textiles are not the only at-risk items for chemical absorption. Wooden cabinets, shelves, or drawers also have the propensity to absorb the harmful chemicals.

In addition to repelling or killing insects such as moths and silverfish, mothballs have been suggested for use as a stovepipe cleaner, a snake repellent, and to keep away mice or other pests. This of course is a terrible suggestion. A quick information search will show you that placing mothballs in the attic, or other areas of your home only results in the family dwelling there to become horribly ill.

Another major concern about the use of mothballs as an animal repellent or poison is their easy access to children, pets, and beneficial animals. Leaving them in a garden or in a living space unprotected makes it very easy for unintended victims to gain access to them. Mothballs are highly toxic when ingested (they have a sweet odor and taste, making this more likely), and will cause serious illness or death.

Now that you have read the above information and never want to use mothballs again, let us talk about the alternatives and why so many people prefer to use safer, more natural remedies to rid themselves of those pesky moth larvae that can eat holes through woolen sweaters, coats, and blankets.

|

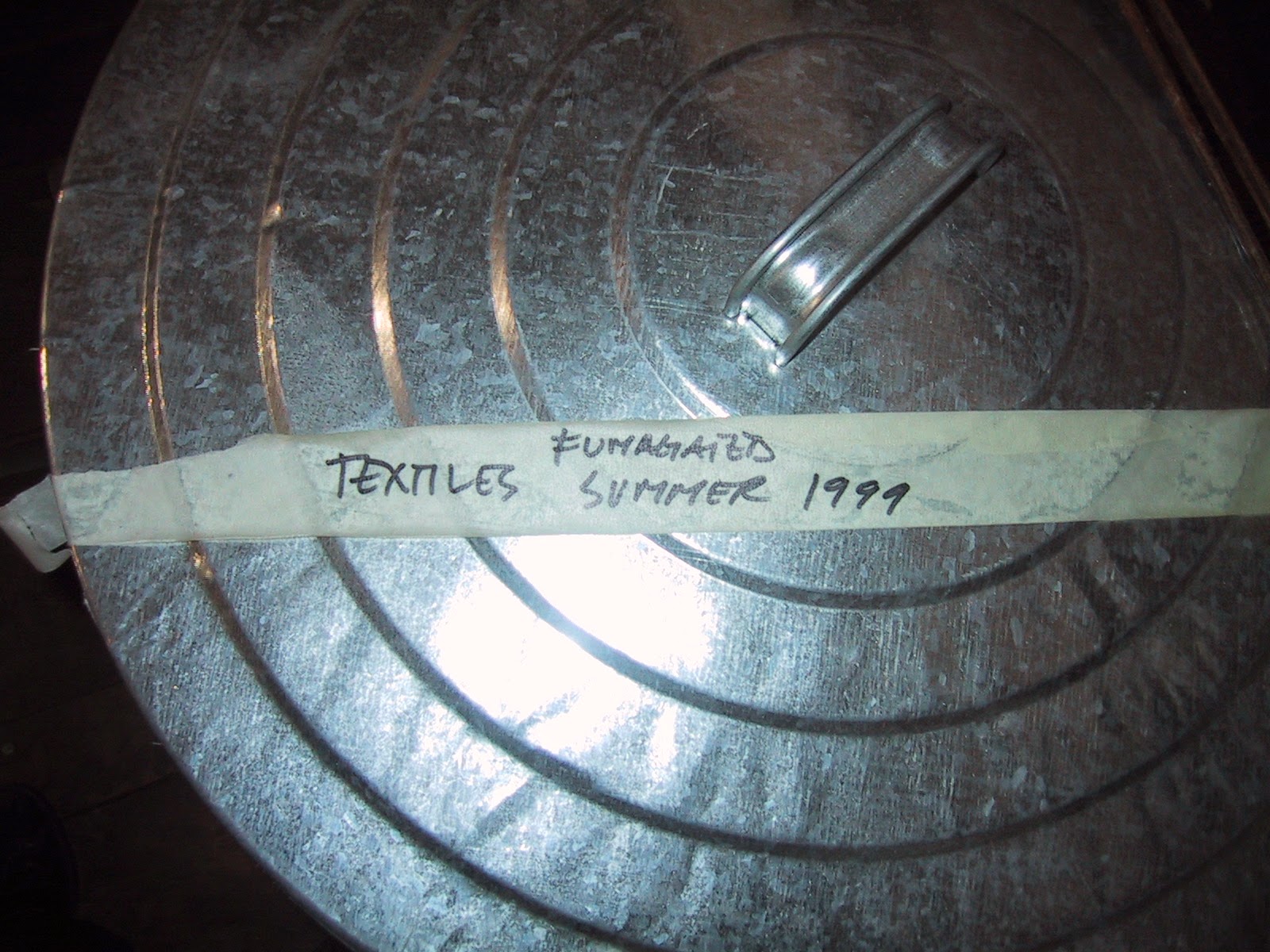

ABOVE and BELOW: These images are from some time ago, but really not so far back in history. The garbage cans are from a museum and the images were taken in 2007. The accepted process, which really stopped being used in the 1980's, was to fill a stainless steel garbage can with the textiles to be stored or "fumigated", add mothballs and seal the can.

|

Alternatives:

Here are some alternatives to help save valued items without resorting to poisonous mothballs or moth crystals. Clearly some options are not for fragile or vulnerable textiles:

Items should be placed in the clothes dryer on a warm cycle to kill any moth eggs, or if possible, periodically air them in the hot sun.

•

Shake out and brush woolen items every three to four weeks (this step may not be practical for all of us, but the following steps certainly are). Clean items prior to storage as moth larvae rely on human soil products, like perspiration residue, for essential vitamins missing from pristine wool.

•

Store clean, off-season items in airtight containers.

•

Freeze infested items in a tightly sealed bag for 48 hours; thaw at room temperature, and repeat. Once fully thawed and dry, seal in an airtight container for storage.

Storing susceptible items in a cedar chest will help reduce damage caused by moths or mold. Cedar oil is a natural repellent of insects like moths; however, many older cedar chests no longer have enough aroma left to do the job. On the other hand, if the chest seals well and smells strongly of cedar, it will probably be a safe place to store items.

Toxin-free alternatives to control clothes moths include freezing, dry cleaning, washing in hot water, or thorough vacuum cleaning.

There is no one-time only procedure for keeping moths at bay. It is only through diligence and monitoring that moths can be kept out of, and off of, wool items. If you have wool items in your collection, inspect them carefully and protect them…but never with mothballs.

So what if you have already used mothballs? Or you are the lucky curator of the museum who just found stainless steel cans hidden in your collection which have not only irreplaceable textiles, but lots of mothballs, and subsequently that horrible mothball smell. The short answer is: Call a Conservator.

|

"Oh, Dear!" Sadly, sometimes valuable or irreplaceable objects are protected with mothballs.

|

_____________________________

Gwen Spicer is a textile conservator in private practice. Spicer Art Conservation specializes in textile conservation, object conservation, and the conservation of works on paper. Gwen's innovative treatment and mounting of flags and textiles is unrivaled. To contact her, please visit her website.