At Spicer Art Conservation, we treat many pastel works of art. Commonly they are portraits, but sometimes the occasional landscape or still life appears.

With few exceptions, the treatment of pastels is focused on the removal of surface mold (Above: before treatment close-up of mold damage on left, at right, overall after treatment photo). For many clients the mold present on their artwork is disfiguring and distracts from the enjoyment of the viewer, but it also serves as a "canary in a coal mine" because mold often grows in a perfect environment where temperature, and relative humidity, along with surface debris or dust has formed the perfect habitat for mold to flourish. If mold has bloomed, the environment has supported it, and if mold has bloomed on one artifact it may happen on others. For museum collections this can be of particular concern as collection are housed together, in one room or space. (Keep in mind that mold loves organic materials and we often see it on artifacts composed of wood, leather, feather, etc.)

|

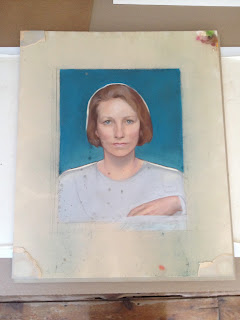

| A pastel portrait after it has been removed from its frame. Here you can see at the lower border edge that the blue pastel particles had fallen behind the mat. |

|

| Closeup image of the mold that has bloomed. |

|

| After treatment, the mold has been neutralized and is not disfiguring. Can it come back? Yes, given the right conditions of temperature, relative humidity, and light, it could grow again. |

|

| After treatment and reframing. Pastels are always framed with glass because the static charge present on plexiglas will have an effect on the small loose particles of pastel dust. |

The number of pastels with mold present far outnumbers any other works of art on paper with mold present. Why is this? The answer lays much in the inherent nature of pastels. Other colored works of art (whether they are paintings or watercolors) all have some portion of binding material that protect the colored pigment. The more binder, the more protection and the more "stable" the pigment vehicle. The more binder also means the more ability for an art conservator to clean the surface. If a large amount of binder is present, the pigment vehicle (oil paint for instance) is more solid. For more information on pigments and their binders see the information below about paint.

|

| The above is a slide from a lecture given by Carl Plansky of Williamsburg Paint. |

Unlike other pigment applications, pastels have almost completely unbounded pigment with the tiniest amount of binder. Mostly the pigment particles simply rest on the surface of the paper. The selection of the paper that some artists use also assists with the adherence of the pastel to the paper, as that there are special rough surfaced papers designed especially for pastels that help to "grab" the pastel particles. But these papers are not always what the artist has used.

George L. Stout of "Monuments Men" fame produced the most effective schematic of illustrating the various types of surfaces and the "tooth" of the media. His illustration, "Classes of Simple Paint Structure" was first produced in Technical Studies Volume VI, 1938, page 231 (Technical Studies later became Studies in Conservation). See below.

From the illustration above, pastel is classified along with chalk and charcoal as granular and loose. What might be harder to read is the arrows near the center of the page which show that as you move from left to right, the absorption and transmission of light is increasing. If you think of looking at a pastel it appears flat, whereas if you look at an oil painting, or even at acrylic paints with a glazed surface, it has reflective properties and might even be described as shiny.

The presence of binders around pigment particles creates different optical effects, and more or less saturation of color. One of the beauties of pastels is the full situation of the pigment, that it is only the pigment that one sees. It is these exposed pigment particles that become the surface from which the mold grows. According to Kit Gentry, "Mold loves pastel. Dense, fluffy, mineral-rich layers of pastel are basically like potting soil for mold". Well said.

Pastels cannot be easily cleaned for a number of reasons, but especially important to the growth of mold is that dirt is attracted to the rough surface (even when protected by a frame with glass or plexiglas). The dirt then becomes a food source for the mold. The challenge then becomes removing the mold without removing the small particles of pigment which are loosely held to the surface and can easily be dislodged from the surface.

Often mold follows a particular path on the pastel, or is isolated to one pastel color, or one particular area. This odd behavior can probably be explained in that mold follows the source of food, so while you may not be able to see it, the "food" is there. Mold can be fluffy, flat, green, white, blue, etc. the variety of colors shapes and configurations tells us that many species are present, and they are opportunistic.

|

| The mold covering this pastel covered the entire surface, it is more noticeable on the dress of the subject because of the dark color. |

The question of why some older pastels do not have the same number of mold outbreaks has been discussed. Some experts believe that the copper, lead, cadmium, and other heavy metals and elements used in the early production of pastels are what keeps mold at bay on these very old drawing and paintings. Apparently these elements are naturally mold resistant, but of course poisonous to humans, and so are not used in the formulation of pastels the way they were in centuries past (that is not to say that pastels no longer contain hazardous materials).

There are important things to know about mold. There are 1,000's of known mold species. Mold is often dormant, not dead. Mold is omnipresent, therefore you will never be without; mold spores are airborne and therefore are in the air we breathe. Mold species have diverse lifestyles and can vary significantly in their tolerance to temperature and humidity.

We have heard from clients with mold affected pastels who say, "but my house is dry, there is no way mold should grow there". Remember, mold can certainly be kept in check, but it can generally bloom (or re-bloom) if relative humidity increases to 50% or higher, and if temperatures increase above 70 degrees F (this environment most certainly describes anyones home). However, we know that mold grows above 39 degrees F (hence is why food is refrigerated below this temperature) AND we know that mold also grows in our refrigerator which is often below 39 degrees F. The point is that mold is opportunistic and some form of it can grow nearly anywhere under any conditions.

|

| The chart above shows the zone for "optimal mold growth" in blue. Also shown is the ideal conditions for artifacts as well as human comfort zone. |

The lesson here for keeping mold away is that pastels must be kept as clean as possible. This might mean reframing a pastel before dirt enters an unsealed frame and therefore before mold even gets the chance to grow. Any torn or broken dust paper at the back of an old frame is an entry point for dirt and debris to find its way into the frame package. Conservators have in the last few years made tremendous progress on methods of framing, creating a sealed archival package around the matted artifact, and then sealing the frame as well. This is really now made possible with truly archival materials. Once created, the sealed package is then secured into the frame (either a new frame or into the original frame). With this method, it is no longer necessary to secure dust papers to the back of the frame (see image below).

Be warned. There are some amazingly frightening suggestions to be found online to offer assistance with getting rid of mold. Including baking your pastel in an oven along with a potato, or spraying it with liquid moth balls, YIKES. A professional art conservator is once again the way to go. Seriously, don't mess around with crazy methods or those which use toxins. Seriously.

Lastly, placing a pastel with mold on it in direct sunlight as a method to deter or disable any mold is not a good idea. While it might disable the mold that is susceptible to light, the light damage to the pigment of the pastel are both cumulative and permanent.

For further reading, The Pastel Society of America has an informative website about everything you want to know about pastels. If you own a pre-1800's pastel, Neil Jeffares book, Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800, talks about everything pastel before the 19th century, including conservation. You can also check out our "Inside the Conservator's Studio" blog posts about Mold in Collections, also our post on Environmental Conditions. Both are informative, but if you have concerns about a pastel and need a conservator to help, please contact us.

_____________________________

Gwen Spicer is a conservator in private practice. Spicer Art Conservation specializes in textile conservation, object conservation, and the conservation of works on paper. To contact Gwen, please visit her website or send an email.

Excellent and very exciting site. Love to watch. Keep Rocking. mold removal companies

ReplyDeletePlease share more like that. mold remediation sarasota

ReplyDelete