Edna St. Vincent Millay in 1914

A conservator's work often entails dealing with art and artifacts that span the spectrum from the truly spectacular to the mundane. All need to be treated with the same respect no matter their type or provenance, and the conservator's training allows her to see and understand the importance of each and every item in her care.

Passing through the conservator's studio a couple of years ago were some everyday objects belonging to one of America's most respected and successful poets. Born in 1892, Edna St. Vincent Millay grew up in a household with a strong, independent mother who took an intense interest in seeing her daughter exposed to a broad and liberal cultural education. Millay flourished in this environment, went on to graduate from Vassar College, and become a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and feminist activist.

Millay spent the last twenty-five years of her life with her husband at their home, called

Steepletop, in Austerlitz, NY. Today the house still holds all of her furniture, her books and other possessions, many of which remain where they were on the day she died in 1950. The site is maintained by the nonprofit Edna St. Vincent Millay Society.

Steepletop as it appears today

Enter the conservator sixty-five years after Millay's death. Three items -- a pastel portrait of Millay, a lampshade, and a Do Not Disturb hotel sign -- were all in need of treatment.

The large portrait (30 x 25 inches) had been executed in 1937 on a dense laminated board by illustrator and portrait painter Neysa McMein for McCall's magazine. Because of Steepletop's humid environment, mold was present, as was staining, on Millay's face and the background. Extensive dirt and debris were found when the frame was opened during initial examination. The goal of the treatment was to compensate for the mold damage and reframe the picture using archival materials. The backing board and matting were removed and discarded, mold residue was removed and the staining was in-painted with a similar type of medium. Reassembly required attaching the portrait to acid-free board with Japanese paper hinges, creating a new window mat of acid-free board, cleaning the frame and adding glass with ultraviolet filtering.

|

| Before and after treatment of Edna's portrait. |

The early 20th century lampshade consisted of six paper panels containing three alternating bird prints. Not only was the shade dirty from coal soot, the metal support at its top had separated from the paper and it had been repaired with tape. It appeared that a coating, possibly to imitate thin wood veneer, had been allied to the panels. Compounding the condition were losses at the edges of the shade and a 3-inch tear with smaller tears radiating out from it. The focus of the treatment was to secure the metal support and mend the tear with Japanese paper and wheat starch paste. Creases and paper distortions were reduced through humidification.

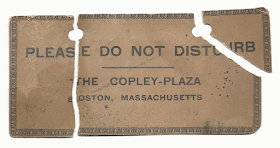

The most curious artifact of all was the circa 1927 paper sign reading "DO NOT DISTURB / THE COPLEY-PLAZA / BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS", which hung from the doorknob by a string. What would be an occasion that would cause someone to keep such a memento? It's interesting that Millay was in Boston along with other writers in August 1927 to protest the verdict of Sacco and Vanzetti and was arrested for her participation. Her prominence afforded her a meeting with the governor where she made the case of Sacco and Vanzetti's innocence. Could a simple hotel sign symbolize such an important event?

|

| Before and after treatment of the sign |

As often happens with ephemera, careless use or storage often get the better of it. The paper had separated into three pieces, there were tears around the string holes, and fragments of the sign had torn away. The cotton string was kinked, creased, knotted and dirty. After cleaning, the sign was reinforced with acid-free board for additional support and the tears were mended with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste. Losses were replaced by toned Japanese tissue and in-painted as necessary. Lastly, a support stand was created for the sign.