|

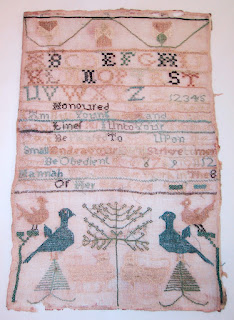

| Pictorial Sampler c. 1876 |

When you talk about samplers, an image is conjured of a

rectangular piece of old linen with a hand-stitched alphabet, or perhaps a

biblical verse, and a “signature” of a girl, perhaps between the ages of 8 and

12 at the bottom, often accompanied by the location of where she lived or went

to school. But the world of

samplers goes far beyond to include intricate, highly skilled pieces such as

mourning pieces, coats of arms, genealogies, pictorial works, and

landscapes. Some feature painted

silk, metallic threads and velvet appliqué.

The underlying history to each sampler is that it is also a

documentation of the education of girls at a time when girls were seldom educated,

and when they were, it was a focus on domestic arts that often dominated their

studies. For it was said in an

early Italian proverb; “A girl should be taught to sew and not to read,

unless one wishes to make a nun of her”.

The study of samplers is an immense field with numerous

texts written on everything from the way a sampler was produced, to similar

sampler themes and elements which make it indicative of a certain region, to

the methods of stitching, and the list goes on and on.

|

| A mourning piece c. 1864. Notice the willow tree? It appears frequently in this kind of sampler. |

SAC has had the pleasure of working on countless samplers

from nearly every decade from the late 1700’s through the mid to late

nineteenth century when the dominance of needlework in education came to a

close. Not to say that samplers

first appeared in the late 1700’s, in fact they begin to appear as a

“graduating accomplishment” in the century before and early samplers can be

traced back to Renaissance times. The late eighteenth to mid nineteenth century was signified by a time

when girls were sent to be “educated” in a way that made them suitable for a

domestic future. Needlework was

clearly important, reading might be taught, however writing was not always

deemed necessary. Girls may also have received

instruction in history or arithmetic, but equally important would be painting,

drawing, and perhaps dancing and piano. This all depended of course on how much a family could afford, or if

they could afford to send a daughter to school at all.

|

| A beautiful pictorial work. Notice the original frame and the painted glass. |

|

| Another pictorial piece prior to conservation. |

While each sampler is different, the conservation of

samplers often presents the same problems. So often a sampler has gotten wet in some way; either it was

stored improperly, damaged in a flood, or the humidity levels were too high. This results in the dye of the thread

beginning to “bleed” into the other colors or on to the linen. Moisture in/on samplers can also lead

to tide marks in the linen.

Damage to samplers can also be “self-inflicted” in that the

thread used to create the sampler contained tannins, which due to their own

acidic nature, became brittle and then disintegrate.

|

| Front side exposed to constant light. |

A sampler that has been displayed for years can also have

light damage. The threads become

faded and the linen darkens. Dust

and dirt collect on the stitches and linen, furthering a dark, faded

appearance. Turning a sampler over

will reveal a glimpse of what it originally looked like. The reverse, particularly on samplers

which are in their original frame, shows the original color of the linen and

the vibrant colors of the thread.

|

| Reverse side that had been protected from light - notice the difference in color. |

Regional samplers come from a particular geographic location and can often be identified simply by what is in the picture. It has been speculated that this is simply because the schoolmistress gave out the same pattern to her students year after year. Particular style elements or unique stitches have been attributed to an individual teacher and can be traced to her as she moved from one school to another, therefore influencing the samplers of the towns in which she taught.

|

| Dudley Castle, which is now the Dudley Observatory in Schenectady, New York |

|

| A mourning piece done in hair? |

The Capital Region of New York has a unique feature to some

of its samplers. Unlike samplers

from other regions, these were worked in a small, fine, stitch that appears

to be a brown or black thread. Here’s the rumor – it is said that the thread is actually the hair of

the girl who created the sampler. Now that’s really putting yourself into your work! If it is hair, shouldn’t there be

“blond” or “red” works?

|

| A close-up of a "traditional" Capital Region piece

_____________________________

Gwen Spicer is a textile conservator in private practice. Spicer Art Conservation specializes in textile conservation, object conservation, and the conservation of works on paper. Gwen's innovative treatment and mounting of flags and textiles is unrivaled. To contact her, please visit her website.

|

What do you think, is it possible, is it probable?